Antarctica 4: Piecing the last jigsaw of Antarctica

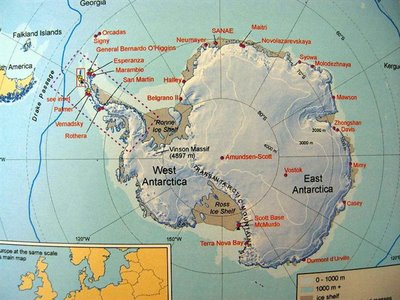

The crossing of the 7-mile Lemaire Channel, widest at 1 mile across and half-a-mile at its narrowest was first navigated by De Gerlache in 1898. Expedition members on this journey made the journey again on Christmas Day, 107 years later - a very short period of time in terms of history.

As such, the crossing was met with much anticipation and excitement. Everyone on board was struck silent just listening to the ice-crushing barge cruising through ice precariously between the twin snowed peaks (below). It reminded me of the blockbuster movie, ‘Jason and the Argonauts’. It was simply awesome!

The finale of the Antarctic expedition came when announcement bellowed through the loudspeaker to prepare for a ‘zodiac’ cruise among the icebergs. With the numerous landings we have had and rehearsed, dressing up for the outdoor became much easier and quicker. Soon, even the senior members were strapping on life jackets expertly, double layered socks inside our boots and were able to waddle smartly up and down staircases and onto awaiting zodiacs in a jiffy.

The finale of the Antarctic expedition came when announcement bellowed through the loudspeaker to prepare for a ‘zodiac’ cruise among the icebergs. With the numerous landings we have had and rehearsed, dressing up for the outdoor became much easier and quicker. Soon, even the senior members were strapping on life jackets expertly, double layered socks inside our boots and were able to waddle smartly up and down staircases and onto awaiting zodiacs in a jiffy.  In complying with strict regulations of the Environmental Protocol, on each returned trip to ship, we had to walk passed a trough of disinfectant solution. Leaned against the edge of the ship, front facing, we lifted our foot behind us, and had our boots water blasted under high pressure jet from a fireman’s hose (above).

In complying with strict regulations of the Environmental Protocol, on each returned trip to ship, we had to walk passed a trough of disinfectant solution. Leaned against the edge of the ship, front facing, we lifted our foot behind us, and had our boots water blasted under high pressure jet from a fireman’s hose (above). Cruising around the ice, this was what we saw.

Ice came in various sizes and formations (above). Some white, some with many hues of blue; there was the green Jade ice, black ice with dimples like orange peel that has been floating in the sea for many, many years. Surfaces of ice carved by ocean currents came in different facets, designs, each unique in appearance and in form. On some icebergs, nature’s frozen platforms were created for crabeater and leopard seals to laze around (below).

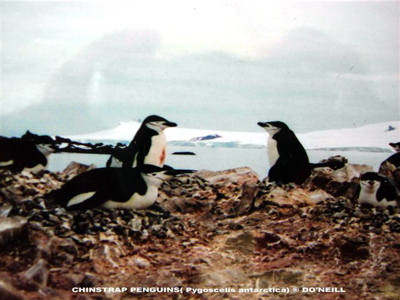

Encrusted on some cliff rocks were nesting colonies of the Antarctic Blue-eyed Shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps), a species of cormorant with a more efficient swimming foot - with web connecting all four toes instead of 3 in most seabirds. They have no external nostril openings and their breeding grounds are often near or among penguin colonies.

Encrusted on some cliff rocks were nesting colonies of the Antarctic Blue-eyed Shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps), a species of cormorant with a more efficient swimming foot - with web connecting all four toes instead of 3 in most seabirds. They have no external nostril openings and their breeding grounds are often near or among penguin colonies.  Another unique species of bird is found here - the ubiquitous Snowy Sheathbill (Chionis alba) – the flying ‘cleaning machine’ of Antarctica (above).

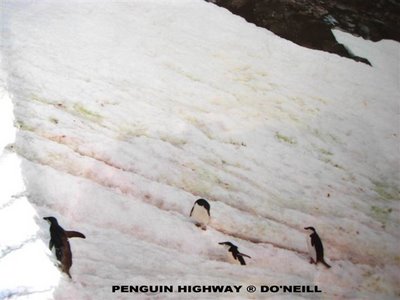

Another unique species of bird is found here - the ubiquitous Snowy Sheathbill (Chionis alba) – the flying ‘cleaning machine’ of Antarctica (above). This pigeon-sized species while appearing white, quiet and innocent looking, is the most conspicuous scavenger of all. They are the flying cleaning machines that gobble up penguin ‘poo’ and thrive on anything organic from carcasses and afterbirths of animals to sucking eggs or even kill life chicks of penguins. With rounded wings, they can swim and when on land, would perch unperturbed, taking their place amongst the penguins in a compromised liaison of recycling.

How does one continue to keep the largest wilderness area on earth relatively pristine yet permitting tourists’ visitations to this ecosystem wonder of nearly 14 million square kilometres? The National Environmental Research Council recorded 10,000 visiting tourists in 1999 alone during the summer season.

Much of the stimuli for Antarctic exploration in the 18th and 19th century were of commercial interests, bringing the Antarctic fur seals to near extinction and an over exploitation of various whale species that ended up in numerous sushi bars.

In 1980, the Antarctic Treaty nations adopted the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, to correct and maintain the populations of all the species in the Southern Ocean marine ecosystem through its strict monitoring and effective fishery management.

Activities in the Antarctic are governed by the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, signed by various nations designating Antarctica to be for peace and science. In 1991, the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties adopted the Protocol on environmental protection designating Antarctica as a natural reserve. It sets principles, procedures and obligations for the comprehensive protection of the white continent and its wildlife within and oceans around.

The Environmental Protocol applies to tourism, governmental and non-governmental activities in the Antarctic Treaty Area ensuring that minimal impact on the Antarctic environments is made as possible.

Hence, the IAATO (International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators) was conceived and began the registration of tour operators to adopt a voluntary code of conduct for visitors to Antarctica. Today, tour operators adhere to strict guidelines and undertake the responsibility to ensure visitors to the continent abide by the set rules as delivered by the expedition cruise company.

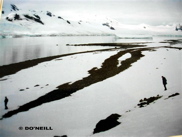

It does not end here. Many works are still being done quietly behind scenes by scientists and researchers on their tour of duties to the continent (above). They claim no glory for themselves but for science. The British Antarctic Survey is one of them and aspires to become the leading international centre for Global Science in the Antarctic context by 2012.

It does not end here. Many works are still being done quietly behind scenes by scientists and researchers on their tour of duties to the continent (above). They claim no glory for themselves but for science. The British Antarctic Survey is one of them and aspires to become the leading international centre for Global Science in the Antarctic context by 2012.Having visited this 7th continent, it is not hard to see who those people are and why they are drawn to this cold, isolated and inhospitable world. One needs either one or all - passion, aloneness and addiction to the wilderness to be able to stay on and want more of it!

To me, it has been an educational field exercise of environmental and soul searching expedition; an open university in evoking the awareness of the importance of environmental conservation in one’s own conscience; of which guarantees no participant failures. It fuels a challenge to put thoughts into practice… a lonely and uphill path to take and few would really succeed.

Global warming is real in Antarctica and every visitor to the continent is a witness to view dramatically, frozen iced cliffs breaking off. The whipping sound of cracked ice was like a gunshot fired across the bay and chunks of ice formed millions of years ago just collapsed and crashed into the sea, creating a tsunami-waves enough to stir and wake a sleepy ocean bay.

By encouraging fellow birding friends to follow one’s own environmental-conscious behaviour; advocating the protection and conservation of important habitats in the world we live in and love the birds that live within; will we hope to contribute, to ensure whatever that is left, remains pristine for the enjoyment of future generations.

Have humans learned from past mistakes or are we continuing to abuse, hack down natures’ wonders as though there is no tomorrow?

Will Antarctica… the final, frontier continent be next to be axed?

SUBMITTED BY DAISY O’NEILL, PENANG, MALAYSIA.

The Antarctica series is dedicated to the memory of my English foster parents - Bert and Phyllis Johnson and to my spouse, James O’Neill, without which this journey could not have been made nor be written.

Labels: Travelogue