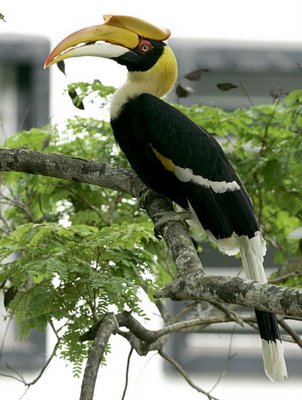

Roost of the Great Hornbill

As far as we know, there is only one Great Hornbill (Buceros bicronis) in Singapore. And this bird is an escapee, probably from the Jurong Bird Park some years ago. For some months now, this bird has paired up with a Rhinoceros Hornbill (B. rhinoceros), another escapee. Two earlier reports (1, 2) give accounts of the activities of these two hornbills prospecting for a nesting cavity in an old albizia tree (Paraserianthes falcataria) around the Eng Neo area. They arrived during most mornings of late February and March 2006, spent half an hour to an hour around the area before leaving. Sometimes they also came during the evenings. Towards late April and May these birds appeared less regularly.

As far as we know, there is only one Great Hornbill (Buceros bicronis) in Singapore. And this bird is an escapee, probably from the Jurong Bird Park some years ago. For some months now, this bird has paired up with a Rhinoceros Hornbill (B. rhinoceros), another escapee. Two earlier reports (1, 2) give accounts of the activities of these two hornbills prospecting for a nesting cavity in an old albizia tree (Paraserianthes falcataria) around the Eng Neo area. They arrived during most mornings of late February and March 2006, spent half an hour to an hour around the area before leaving. Sometimes they also came during the evenings. Towards late April and May these birds appeared less regularly.We have always wondered where the birds ended up at night. At last we have part of the answer.

Brian Ng alerted me of a Great Hornbill that regularly arrived every evening around 7.00 to 7.15 pm to spend the night on a branch of a rain tree (Samanea saman) outside his fifth level apartment window around Adam Road. The hornbill stayed all night in this tree but come morning, usually around 6.45 to 7.00 am, it started moving, stretching its wings and preening before flying towards Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Or that was what Brian thought.

But I think it flew to nearby Eng Neo where it met up with the Rhinoceros Hornbill.

The Great was always alone at the roost. And Brian never saw the presence of the Rhinoceros. Now where can the Rhinoceros be roosting at night?

Towards the end of April onwards the bird visited less regularly, coinciding with its irregular visits to the Eng Neo area. Brian has since confirmed (30th May 2006) that "The Great hasn't returned... in the past weeks..."

Thanks Brian for the alert. Image by Chan Yoke Meng.

Brian’s video can be viewed here.

Labels: Hornbills